It’s mid-afternoon along Medellín’s Avenida Oriental, a traffic-clogged road that scythes through the heart of the second largest Colombian city, and Nicolas Pineda is crouched down on his haunches as cars zoom by on both sides.

Wrapped up in heavy duty workwear and armed with a machete, Pineda is weeding a thick strip of tree-lined greenery running between the lanes. He hacks at a patch of dead, browning bush and then pulls up a rogue, zig zag-shaped shrub beside his foot.

“Es bien bonita,” grins the 54-year-old, evidently pleased with his handiwork. “It’s very clean. That’s what I like to see: a clean, green city.”

Pineda has helped to sow and maintain hundreds of thousands of trees and plants across Medellín as part of a people-led scheme to fight back against extreme heat through a network of “Green Corridors” across the city.

In the face of a rapidly heating planet, the City of Eternal Spring — nicknamed so thanks to its year-round temperate climate — has found a way to keep its cool.

Previously, Medellín had undergone years of rapid urban expansion, which led to a severe urban heat island effect — raising temperatures in the city to significantly higher than in the surrounding suburban and rural areas. Roads and other concrete infrastructure absorb and maintain the sun’s heat for much longer than green infrastructure.

“Medellín grew at the expense of green spaces and vegetation,” says Pilar Vargas, a forest engineer working for City Hall. “We built and built and built. There wasn’t a lot of thought about the impact on the climate. It became obvious that had to change.”

Efforts began in 2016 under Medellín’s then mayor, Federico Gutiérrez (who, after completing one term in 2019, was re-elected at the end of 2023). The city launched a new approach to its urban development — one that focused on people and plants.

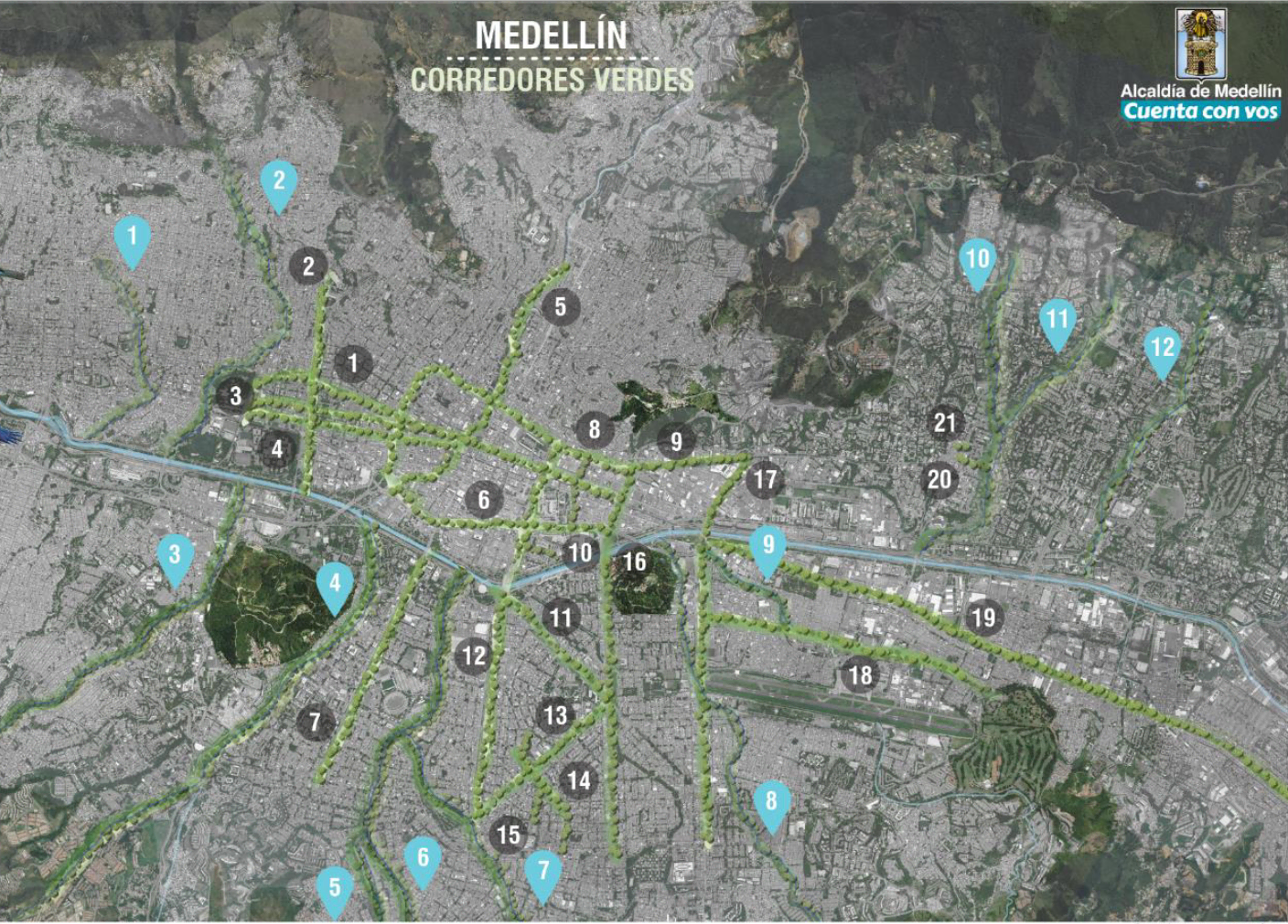

The $16.3 million initiative led to the creation of 30 Green Corridors along the city’s roads and waterways, improving or producing more than 70 hectares of green space, which includes 20 kilometers of shaded routes with cycle lanes and pedestrian paths.

These plant and tree-filled spaces — which connect all sorts of green areas such as the curb strips, squares, parks, vertical gardens, sidewalks, and even some of the seven hills that surround the city — produce fresh, cooling air in the face of urban heat. The corridors are also designed to mimic a natural forest with levels of low, medium and high plants, including native and tropical plants, bamboo grasses and palm trees.

Heat-trapping infrastructure like metro stations and bridges has also been greened as part of the project and government buildings have been adorned with green roofs and vertical gardens to beat the heat. The first of those was installed at Medellín’s City Hall, where nearly 100,000 plants and 12 species span the 1,810 square meter surface.

“It’s like urban acupuncture,” says Paula Zapata, advisor for Medellín at C40 Cities, a global network of about 100 of the world’s leading mayors. “The city is making these small interventions that together act to make a big impact.”

At the launch of the project, 120,000 individual plants and 12,500 trees were added to roads and parks across the city. By 2021, the figure had reached 2.5 million plants and 880,000 trees. Each has been carefully chosen to maximize their impact.

“The technical team thought a lot about the species used. They selected endemic ones that have a functional use,” explains Zapata.

The 72 species of plants and trees selected provide food for wildlife, help biodiversity to spread and fight air pollution. A study, for example, identified Mangifera indica as the best among six plant species found in Medellín at absorbing PM2.5 pollution — particulate matter that can cause asthma, bronchitis and heart disease — and surviving in polluted areas due to its “biochemical and biological mechanisms.”

And the urban planting continues to this day.

The groundwork is carried out by 150 citizen-gardeners like Pineda, who come from disadvantaged and minority backgrounds, with the support of 15 specialized forest engineers. Pineda is now the leader of a team of seven other gardeners who attend to corridors all across the city, shifting depending on the current priorities.

One of them is Victoria Perez. Back at the Avenida Oriental, where 2.3 kilometers of paving has been replaced by gardens, she is pruning a brush. The 40-year-old, like all of the other gardeners in the Green Corridors project, received training by experts from Medellín’s Joaquin Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden.

“I’m completely in favor of the corridors,” says Perez, who grew up in a poor suburb in the city of 2.5 million people. “It really improves the quality of life here.”

Wilmar Jesus, a 48-year-old Afro-Colombian farmer on his first day of the job, is pleased about the project’s possibilities for his own future. “I want to learn more and become better,” he says. “This gives me the opportunity to advance myself.”

The project’s wider impacts are like a breath of fresh air. Medellín’s temperatures fell by 2°C in the first three years of the program, and officials expect a further decrease of 4 to 5C over the next few decades, even taking into account climate change. In turn, City Hall says this will minimize the need for energy-intensive air conditioning.

Going forward, preventing and adapting to hotter temperatures will be a major and urgent challenge for cities. The number of cities exposed to “extreme temperatures” is set to triple over the next decades, according to C40 Cities. By 2050, more than 970 cities will experience average summertime temperature highs of 35°C (95°F).

A separate study estimated that in just one of Medellín’s corridors, the new vegetation growth would absorb 160,787 kg of CO2 per year and that over the next century 2,308,505 kg of CO2 will be taken up – roughly the equivalent of taking 500 cars off the road.

In addition, the project has had a significant impact on air pollution. Between 2016 and 2019, the level of PM2.5 fell significantly, and in turn the city’s morbidity rate from acute respiratory infections decreased from 159.8 to 95.3 per 1,000 people.

There’s also been a 34.6 percent rise in cycling in the city, likely due to the new bike paths built for the project, and biodiversity studies show that wildlife is coming back — one sample of five Green Corridors identified 30 different species of butterfly.

Other cities are already taking note. Bogotá and Barranquilla have adopted similar plans, among other Colombian cities, and last year São Paulo, Brazil, the largest city in South America, began expanding its corridors after launching them in 2022.

“For sure, Green Corridors could work in many other places,” says Zapata.

But there are some challenges. The corridors in the inner city areas have to contend with huge amounts of pollution as traffic piles up. Often drivers will also dump trash along the corridors. And the city’s homeless are forced to take shelter in the spaces.

“Like anything, nature requires maintenance from time to time,” adds Zapata. “You need to allocate a part of the budget for this.”

The previous administration “didn’t give enough money” to maintain the corridors properly, says Zapata, meaning some parts have become overgrown and dirty.

That’s a particularly tricky issue as the city now finds itself $2.8 billion in debt. Maintaining the city’s green corridors costs $625,000 a year, according to City Hall.

But now that he’s back in office, Mayor Gutiérrez has pledged to reinvigorate the project of urban planting. And experimentation with new technology, such as “geotextile” pavements that can soak up rain and bend to allow tree roots to spread, is already underway.

“The plan is to plant more Green Corridors and link them to even more hills and streams, recovering what we have already planted,” Gutiérrez tells Reasons to be Cheerful. “It will be a more green Medellín.”